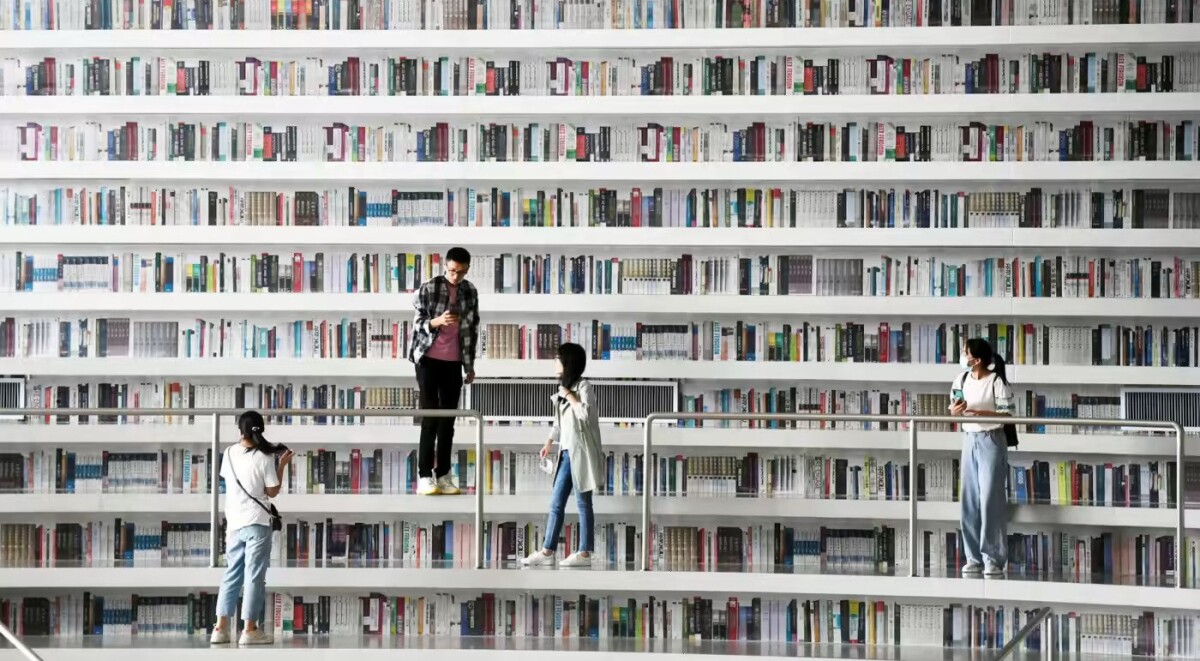

ABOVE: the landmark Tianjin Binhai New Area Library in Tianjin, northern China

From printing press to internet, technology has driven the way we store the written word. But what are we at risk of losing?

12 December 2020 – Richard Ovenden, head of the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, recently wrote:

As a librarian, one of my dearest wishes would be to receive a pound for each time I have been told that libraries are obsolete and will be redundant by the end of the decade. If that wish had been granted when I began my career, I could surely by now have replaced £500 from the Bodleian Library’s endowment, which was “loaned” to Charles I in the 1642 — and was then worth about 20 years of a skilled tradesman’s employment.

The enduring vitality and importance of libraries is underscored by the arrival of two timely new books. They address both the history and future challenges facing these important institutions. Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen take a broad view in “The Library, ranging across the millenia. Meanwhile in Bitstreams, Matthew Kirschenbaum, professor of digital humanities at the University of Maryland, focuses on the growing issue of how, in our digital world, we can ensure the future preservation and understanding of literary texts.

Pettegree and Weduwen, both historians at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, begin their survey in the libraries of the ancient world, but deal with these and with medieval libraries fairly swiftly before focusing on early modern Europe. They cover with great skill the impact of the twin phenomena of the Reformation and the invention of printing by moveable type in the west.

The explosion in the availability and circulation of texts in print that followed created two profound challenges for European libraries from the mid-15th century onwards. Pressure on space led to the building of bigger and more sophisticated buildings, and the growth of available knowledge led to a more philosophical response, as libraries and librarians had to face the issues of selection and access.

When the universe of knowledge becomes so great, and resources are limited, policies are needed to help choose what to acquire and what to leave aside. With ever-bigger bodies of knowledge to care for, libraries have to create their own technologies to enable users to navigate towards the material they need: namely, catalogues and schemes of subject classification.

The authors allow us to eavesdrop on a future pope’s excited discovery of Gutenberg’s new technology, and we encounter some of the great libraries of the age (now little known outside the cognoscenti). These include the one established by Fernando Colón, son of Christopher Columbus, who founded what the authors regarded as the greatest collection of the early modern world, still accessible in the Cathedral of Seville. There’s also the library of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, full of cutting-edge humanistic learning, but now dispersed across many libraries in Europe and North America. I also learnt something new about my own library (the Bodleian in Oxford): our founder’s emphasis on silence was arguably the earliest stricture of its kind.

As the authors approach our current era, the history of libraries takes a different turn — especially from the middle of the 19th century when the public library movement began. In England, the Public Libraries Act of 1850 was the game-changer, and through a combination of state policy and private philanthropy (most memorably by Andrew Carnegie), many western societies, and those in their colonies, developed networks of free public libraries. These are now sadly threatened by short-termist thinking at governmental level, ignoring their role as essential social infrastructure.

Most writers now compose their texts using word-processing software, the development of which was the focus of Matthew Kirschenbaum’s earlier brilliant work “Track Changes” (2016). The use of digital technologies for both the composition and dissemination of literary texts was the subject of his 2016 Rosenbach Lectures, published impressively soon after they were delivered.

In “Bitstreams”, Kirschenbaum spotlights the highly distributed nature of literary creation in a networked age, where a multiplicity of online platforms — social media, blogs, private email accounts — in addition to the range of devices used by a writer (or reader) confuse and complicate the way in which the literature can be understood, comprehended and passed on to future generations.

If librarians and scholars in the past complained of the multiplicity of knowledge, the task facing their successors is even more complex. Above all, despite the ease with which we can access cloud services, free software and storage, Kirschenbaum reminds us that digital texts — especially literary texts — remain “material” in many ways: reassuringly ephemeral, fragile, and subject to all manner of human foibles and frailties that will affect their ability to be read and understood long into the future.

At the end of “The Library”, the authors link the future success of libraries to the future of the physical book. Although I don’t think the physical book will disappear any time soon, in “Bitstreams” Kirschenbaum points out that the shift to digital creation and interaction with the text has now moved so far that libraries and scholars are creating new ways to ensure that society can study and appreciate the literature being created today.

One of the best things about Pettegree and Weduven’s long and engrossing survey of the library is that they show how adaptable and creative libraries have been over time. I have no doubt that future histories will continue to tell that story.